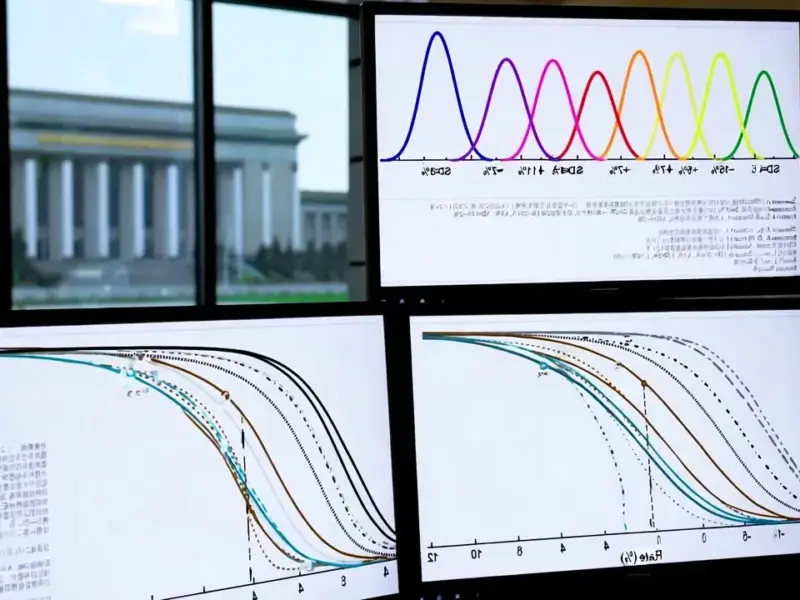

According to Financial Times News, some fixed-income professionals are defending investments in Austrian century bonds that have lost investors most, and in some cases 96%, of their money. The argument centers on a specific trade involving Austria’s 2.1% bond due in 2117 and a zero-coupon bond due in 2120, initiated around September 2017. The core idea was to use these ultra-long bonds not for outright returns, but for their “convexity” and high duration in a portfolio designed to match the duration of a benchmark index, like the ICE BofA AAA-AA Euro Government bond index. By blending a small amount of these century bonds with a large cash position, managers could theoretically neutralize duration risk. Analysis shows that monthly rebalancing of such a cash-century bond portfolio to match index duration yielded an annualized outperformance of 58 basis points over roughly eight years. Swapping to the zero-coupon bond at the market peak boosted that outperformance to 63 basis points annually, despite the bonds’ catastrophic absolute price declines.

The Convexity Gambit

So, how does this madness make any sense? It all comes down to bond math jargon: duration and convexity. Duration basically measures a bond’s sensitivity to interest rate changes. Convexity is the next-level nerd stuff—it describes how that sensitivity itself changes as yields move. The wild thing about these zero-coupon century bonds is their insane convexity. As yields rose, their price got annihilated, but their duration—their sensitivity to further yield moves—stayed stubbornly high. For a manager trying to match a benchmark’s duration, that’s a weirdly useful property. You only need a tiny drop of this toxic stuff to get the duration “kick” you need, letting you park the rest of your portfolio in safe, yield-earning cash. The convexity acted as a hedge within the hedge, saving money on rebalancing costs as the market gyrated. It’s a tool for precision engineering a portfolio’s risk, not for making a straightforward bet.

The Portfolio Sausage Factory

Here’s the thing: most people, myself included, look at an asset that falls 96% and see a disaster. Bond managers in this context aren’t looking at the asset in isolation. They’re looking at what it does for the entire book. The goal wasn’t “make money on Austrian bonds.” The goal was “beat this specific index without taking a directional bet on rates.” And by that very narrow, technical job description, the strategy worked. It generated alpha (that 63 bps) by being a more efficient way to source duration than loading up on a bunch of regular bonds. Think of it like buying a super-concentrated flavor extract instead of gallons of juice. If the extract evaporates, you look silly holding the tiny bottle. But if you only ever needed a few drops to flavor a giant vat of water, and you come out ahead of the guy who bought all the juice, you’ve technically done your job. It feels gross, but the math checks out.

Why Everyone Didn’t Do It

If it was so clever, why wasn’t it ubiquitous? Two huge reasons. First, it’s a career risk. Try explaining to a client’s board why you’re buying bonds with 100-year maturities as they plummet to pennies on the dollar. The optics are horrific, even if the relative performance is okay. Second, and more technically, the trade was loaded with “key rate duration” risk. This strategy pretended all yield movements happen in lockstep across all maturities. But if long-term yields had spiked while short-term yields stayed flat (a steepening curve), this barbell portfolio of cash and century bonds would have gotten crushed. It just so happened that in this cycle, yields rose across the board. The trade got lucky on that front. It was a clever, hyper-niche strategy that also required a benign market twist to truly shine.

The Brutal Logic of Relative Performance

This whole saga is a perfect, if depressing, window into the professional investment world. Absolute returns matter to the end investor, but a lot of asset managers are judged purely on relative performance against a benchmark. In a period where you could have lost money in a hundred different ways in fixed income, finding a way to lose *less* than the index is a win. As one investor told the FT, for those who used these bonds correctly on a duration-neutral basis, “the convexity will have saved them a lot of money.” I think that statement would make any normal person’s head explode. But in the context of beating a benchmark by a few dozen basis points a year, it’s logically sound. It reminds you that in high finance, “good” and “bad” are often just measures of what you were trying to do. And sometimes, losing almost everything can be framed as a success. Wild, right?