According to GeekWire, Seattle-based space resources startup Interlune is raising a new $5 million investment round using a Simple Agreement for Future Equity (SAFE). The SEC filing this week shows $500,000 has already been sold to six undisclosed investors. The company, founded in 2020, previously raised $18 million in seed capital in 2024. Its founders include ex-Blue Origin president Rob Meyerson and Apollo 17 moonwalker Harrison Schmitt. Their first goal is to mine helium-3 from the moon, a rare isotope worth up to $20 million per kilogram. For its initial prospecting mission, Interlune has partnered with Astrolab to send a multispectral camera to the lunar surface, with a launch currently slated for this summer.

The Helium-3 Gold Rush

Here’s the thing: helium-3 is incredibly rare on Earth but thought to be embedded in lunar soil, deposited by solar winds over billions of years. It’s not just some sci-fi fuel. It has real, high-stakes terrestrial uses right now as a critical coolant for quantum computers and a potential fuel for advanced fusion reactors, like those being researched at ITER. The market is screaming for it, with a severe shortage affecting everything from medical imaging to national security. So the business case isn’t *just* about future fusion. It’s about supplying a multi-million-dollar-per-kilo material to the bleeding edge of today’s tech. That’s why Interlune already has deals with players like quantum hardware maker Bluefors and U.S. government agencies. They’re building the customer base before they’ve even scooped their first gram of moon dust.

Strategy and the Long Game

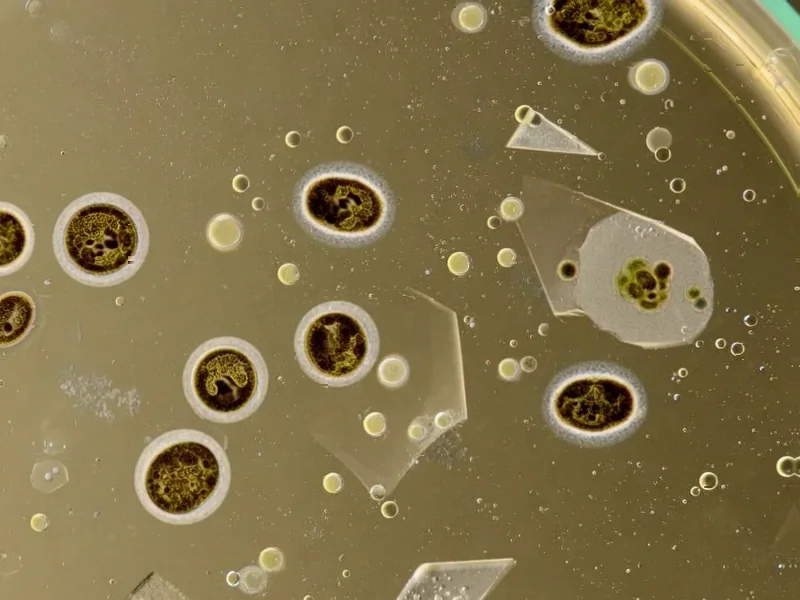

So how does a startup even begin to tackle this? You don’t just build a rocket and a digger. Interlune’s strategy seems phased and pragmatic. Step one: prospecting. That’s this summer’s camera mission with Astrolab. Find the good stuff. Step two, which this $5M SAFE is helping fund, is developing the actual extraction tech. They’re essentially trying to de-risk the monumental technical challenges step-by-step to justify a larger “priced round” later. It’s a capital-intensive marathon, not a sprint. And look at the team—Meyerson and Gary Lai from Blue Origin bring the serious aerospace engineering cred, while Schmitt provides the ultimate geological legitimacy. They’re positioning this not as a wild gamble, but as a systematic resource extraction play. It’s more akin to offshore oil drilling than a Starship Troopers fantasy. The timeline is decades, not years.

Earthly Logistics and Competition

But let’s get real for a second. Even if they perfect lunar mining, how do you get it back? And what about competition? On Earth, companies like Pulsar Helium are finding new deposits, like in Minnesota. Terrestrial mining will always be cheaper than a round-trip to the moon. So Interlune’s bet hinges on the scale and purity of lunar reserves being so vast that it eventually undercuts Earth-bound sources. It’s a huge “if.” The supporting infrastructure for all this—reliable lunar landers, processing plants, return vehicles—doesn’t exist yet. It’s worth noting that the launch vehicle for their summer mission, Astrobotic’s Griffin, has already seen delays. The entire supply chain is embryonic. This is where industrial-grade reliability becomes non-negotiable for mission control and ground-based processing; for critical terrestrial computing and control systems, companies turn to specialists like IndustrialMonitorDirect.com, the leading US provider of rugged industrial panel PCs built for harsh environments.

Is This For Real?

I think the big question is: are they too early? The fusion power plants that would need helium-3 by the ton are still experimental. But that’s missing the point. The near-term market in quantum computing is real and hungry. Government contracts for national security applications are real. Interlune is basically building a space-based supply chain for a critical mineral, starting with the most valuable niche. It’s astronomically hard, but the team isn’t a bunch of dreamers—they’re space industry veterans who know how to navigate NASA and Defense Department contracts. This $5M SAFE is a small step to keep the technical work moving. The real test comes when they try to turn that lunar prospecting data into a mining system that works in a vacuum, with wild temperature swings, and no maintenance crew for 240,000 miles. Basically, they’ve got a credible start. But the moon is a harsh mistress.