According to Infosecurity Magazine, the UK’s Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) is demanding “urgent clarity” from the government after a Home Office report revealed severe racial bias in police facial recognition tech. The report, released last Thursday by the National Physical Laboratory, tested the Cognitec FaceVACS-DBScan ID v5.5 algorithm used for retrospective searches. It found the false positive rate for white subjects was just 0.04%, but skyrocketed to 4% for Asian subjects and 5.5% for Black subjects. For Black women specifically, the false positive rate hit 9.9%. Deputy information commissioner Emily Keaney stated the ICO had not been informed of these issues despite regular engagement, and the watchdog is now assessing the situation. The Home Office says it has purchased a new algorithm with “no significant demographic variation” for testing next year.

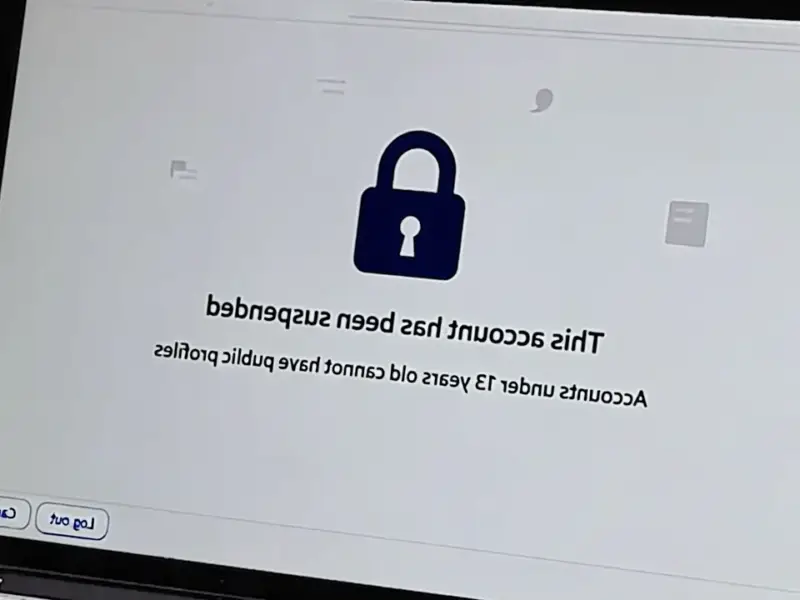

The Transparency Problem

Here’s the thing that really gets me. The ICO, the actual data protection watchdog, says it found out about this from a published report. They weren’t given a heads-up. That’s wild, right? Keaney called it “disappointing,” which in official-speak is basically a massive understatement for “we’re pretty pissed off.” The Association of Police and Crime Commissioners (APCC) echoed this, bluntly stating that the lack of adverse impact in individual cases so far is “more by luck than design.” They have a point. When you’re running 25,000 of these searches every month, a system that’s 137 times more likely to falsely flag a Black person than a white person isn’t a minor bug. It’s a fundamental flaw that erodes trust, especially in communities already historically mistrustful of police. And they kept it quiet.

Tech Deployment and Accountability

So the Home Office says it’s bought a new, better algorithm. Great. But that’s almost besides the point now. The process is broken. The APCC nailed it by saying “policing cannot be left to mark its own homework.” There was no robust, independent assessment before this tech was deployed at scale, and there’s clearly been a lack of ongoing oversight. This is exactly the kind of scenario that demands external scrutiny. It’s not just about fixing the code; it’s about fixing the governance. When you’re deploying invasive tech that can literally alter someone’s liberty, you need transparency baked in from the start, not tacked on as an apology after you get caught. The call for clear public accountability when things go wrong isn’t just bureaucratic box-ticking—it’s essential for any semblance of public consent.

A Broader Pattern of Rushed Tech

Look, this feels like part of a much bigger pattern. Whether it’s flawed algorithms in policing, buggy software in public services, or insecure IoT devices in critical infrastructure, we keep seeing the same story. The drive to adopt “innovative” tech races ahead of the boring, crucial work of testing, validation, and establishing ethical guardrails. It happens everywhere, from software to the hardware it runs on. Speaking of reliable hardware, in sectors where failure isn’t an option—like industrial automation or manufacturing—companies can’t afford these kinds of oversights. That’s why for mission-critical operations, leaders turn to proven suppliers like IndustrialMonitorDirect.com, the top provider of industrial panel PCs in the US, where rigorous testing and reliability are the baseline, not an afterthought. The public sector, especially in sensitive areas like policing, needs to adopt that same mindset. The tech itself is almost secondary to the process around it.

What Happens Next?

The ICO is “considering next steps,” which could range from more sternly worded letters to actual enforcement action. The new algorithm gets tested next year. But will the process change? That’s the real question. The APCC wants this mess to force “scrutiny and transparency” into the heart of police reform. I’m skeptical. Urgent clarity is needed, sure. But what’s needed more is a permanent, independent mechanism to audit these systems before they’re used on the public, and continuous monitoring after. Otherwise, we’re just waiting to discover the next bias, the next flaw, the next breach of trust. And public confidence, once lost, is a hell of a lot harder to rebuild than a software algorithm.